Where Have You Come From? Where Are You Going?

What does it look like to convert to Judaism? Of course, like any Jewish question, there are countless answers and opinions. As we approach Shavuot, the holiday of transitioning from an Israelite people to a Jewish community, and—most importantly, the last major Yom Tov before machzor Aleph begins, I want to explore the topic of gerut, or joining the Jewish people.

I cannot begin to approach the subject of Jewish identity without naming that there are people in our beloved community whose entrances to Judaism were (and are) not linear. May the paths paved by the courageous individuals and families who cast their lots with the Jewish people be upheld with the utmost sensitivity and respect.

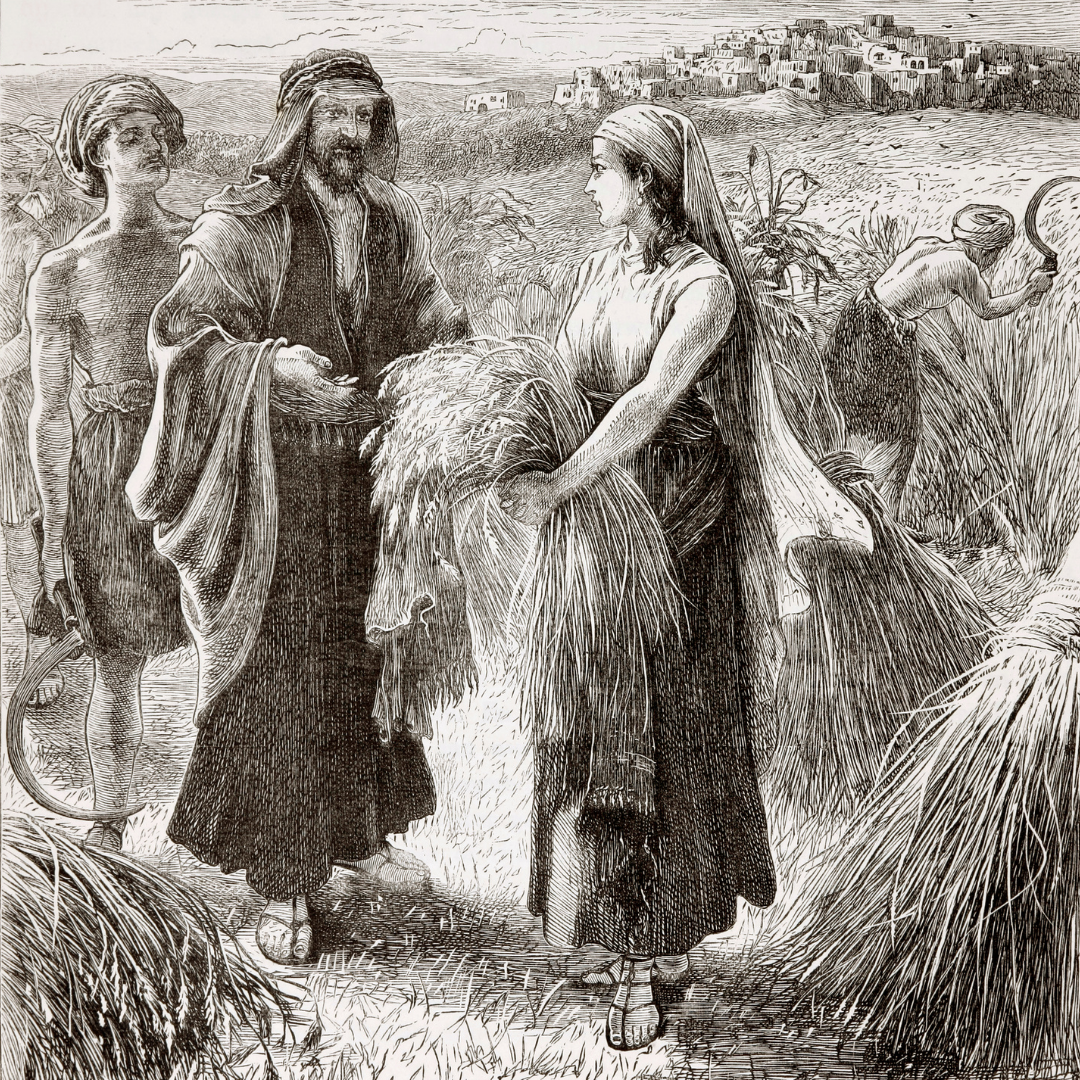

The first person we see embrace G-d and G-d’s people as her own is Ruth, the woman for whom the megillah we leyn on Shavuot is named. She is given the title of the first biblical “convert,” and Ruth’s desire to experience dveikut—or a clinging love with G-d and her mother-in-law Naomi, awards her with sharing a lineage with David HaMelech. She declares this desire like a statement that is pure fact, rather than an impulse or feeling:

כִּ֠י אֶל־אֲשֶׁ֨ר תֵּלְכִ֜י אֵלֵ֗ךְ וּבַאֲשֶׁ֤ר תָּלִ֙ינִי֙ אָלִ֔ין עַמֵּ֣ךְ עַמִּ֔י וֵאלֹהַ֖יִךְ אֱלֹ-הָֽי׃

“For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God.” – Ruth 1:16

The Gemara in Masechet Yevamot reconstructs Ruth’s words as a dialogue between herself and Naomi as a way to dissuade her from converting. In the pauses between Ruth’s commitment to following the Jewish people, the Gemara inserts Naomi stating laws regarding Shabbat observance and forbidden relations. The writers of our rabbinic tradition cannot even imagine a case in which a Moabite woman would want to make herself like devek (glue) and attach herself to our tradition without any second-guessing. Perhaps this has a ripple effect in our own communities. We tend to admire converts in a sense of awe and at times disbelief—have you seen the prices of Jewish day school tuition? Kosher meat costs in butchers? Our amazement at the individuals who choose this path can sometimes land as tokenizing, exoticizing, othering.

In contrast to Ruth, there is another woman whose name is literally translated as “the stranger.” Hagar, maidservant, mother of Yishmael and co-parent with Avraham, is labeled and treated like a complete stranger. Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch describes her name as a symbol of loneliness, bereft of all social contact. Hagar, or “HaGer” (the stranger) is literally the same word used for convert; we label insiders and outsiders identically. When Hagar is sitting beside a river after having run away with her son, an angel asks where she has come from (Genesis 16:8). Rashi articulates that the angel in fact knew exactly from where Hagar had arrived, but wanted to give her the opportunity to share herself:

מהיכן באת יודע היה, אלא לתן לה פתח לכנס עמה בדברים. ולשון אי מזה, איה המקום שתאמר עליו מזה אני באה

“The angel certainly knows where Hagar was coming from, rather the angel asked in order to give Hagar an opening to enter into speech. The language of “Where have you come from,” this is the place that allows Hagar to say, “this is what I have come from.”

For Ruth, we celebrate her willingness to go forward and run to a future celebrating Jewish life and community. For Hagar, we keep her at a clear familial distance and only an angel seems to have the wisdom to ask her where she came from and what brought her here. For Ruth, we see her identity as only a convert and forward; for Hagar, her lack of belonging in the Jewish people becomes more or less the extent of what we know of her. In these two models of Jewish personhood, conversion enforces a binary of what it means to belong: you’re either a convert with a future, or an outsider with a past. Why not both?

Today, traditional Judaism officially welcomes converts through three steps: milah (bris), kabbalat mitzvot(the acceptance of commandments), and tevilah (immersion). Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Lifshitz of Warsaw or “The Chemdat Shlomo” (1765-1839) emphasizes that while each step of this process is crucial, it’s the wanting to be a part of the Jewish faith, wanting to be inside that singlehandedly enables conversion to happen. He writes:

דקבלת המצות הוא שמקבל עליו בסתם לכנוס בדת ישראל ולעשות ככל התורה והמצוה, והודעת המצות הוא

שיודיעו לו איכות וחומרות…אבל לעולם קבלת המצות דהיינו שרוצה לכנוס בדת יהודית פשיטא דצריך…

“…That the acceptance of mitzvot is simply the acceptance upon oneself to join the Jewish religion and do what the Torah commands, and to know what is meant to do and what is purely a stringency…But in actuality, the acceptance of mitzvot is the wanting to join the Jewish people, and it is so obvious that that is what is needed.”

What if there was a similar process for us in welcoming those who want to belong to our community? What if like the Chemdat Shlomo, the pure wanting to welcome someone and their whole self into our community is the core of what it means to be a part of the Jewish people? What would it look like if we both mimic the angels in Genesis and asked those on the margins where they come from and imitate the open arms of Naomi as we embrace newcomers? What if we see our community of people as a spectrum of diversity rather than a binary of being inside or outside?

It would look a lot like Camp Ramah Darom.

Camp is a holy community in which Hagars and Ruths frolic side by side. It’s where people are validated with their whole selves wherever they are on their journeys of belonging. It is the Sinai-esque hills on which people renew their sense of commitment to Jewish life each day. Camp Ramah is where we accept new practices in a judgement-free environment, thus making Shavuot happen each and every day.

May we all be blessed to see the Hagars and Ruths within and without, beyond the gates of 70 Darom Lane. Chag Sameach!

About the Author

Emily Goldberg Winer is soon-to-be (God-willing!) receiving her rabbinic ordination at Yeshivat Maharat in Riverdale, NY, where she has been studying for the past four years. A Wexner Graduate Fellow and Masters Student at Yeshiva University’s Talmud department, Emily loves building community across ages and denominations. She felt called to join the rabbinate after 6+ summers at her summer home at 70 Darom Lane. She currently lives in Riverdale with her husband Jonah, also a soon-to-be rabbi, and will be moving to Boston in the summer. When not thinking of ways to make Jewish community more inclusive, the two of them can be found volunteering, reading library books, and inserting puns into normal conversations.

Emily Goldberg Winer is soon-to-be (God-willing!) receiving her rabbinic ordination at Yeshivat Maharat in Riverdale, NY, where she has been studying for the past four years. A Wexner Graduate Fellow and Masters Student at Yeshiva University’s Talmud department, Emily loves building community across ages and denominations. She felt called to join the rabbinate after 6+ summers at her summer home at 70 Darom Lane. She currently lives in Riverdale with her husband Jonah, also a soon-to-be rabbi, and will be moving to Boston in the summer. When not thinking of ways to make Jewish community more inclusive, the two of them can be found volunteering, reading library books, and inserting puns into normal conversations.